In an illuminating lecture, Professor Wakelin (Jeremy Griffiths Professor of Medieval English Palaeography; Fellow, St Hilda's College) explored the rich and often overlooked world of everyday writing in late medieval England. His research sheds light on how non-literary documents—letters, accounts, legal records, and more—played a crucial role in shaping the English language and offer unique insights into the lived experiences of people from the past.

The First Englishman with a Face

The lecture opened with the intriguing figure of Edward Grimstone, the first non-royal Englishman to have his portrait painted in the 1440s. Beyond his visual likeness, Grimstone’s identity is preserved through his own words in surviving letters. These documents, particularly one in which he defended himself against accusations of financial misconduct, illustrate how handwriting and personal documentation were vital in constructing identity and trustworthiness. Before the advent of print, all books and official records were handwritten, making the study of these texts essential for understanding literacy and authorship in medieval England.

A Revolution in Everyday Writing

For centuries, administrative and legal documents in England were written predominantly in Latin and, following the Norman Conquest, French. However, beginning in the early 1400s, there was a shift towards English. Professor Wakelin highlighted this change, noting that by the end of the 15th century, English had become the dominant language for personal and municipal records. Letters were the first genre to transition, likely due to their personal nature, followed by town ordinances, medical manuals, and legal statements. This shift was not necessarily political but practical—writers were choosing English for clarity and precision, particularly when dealing with complex subjects such as trade, local governance, and even food inventories.

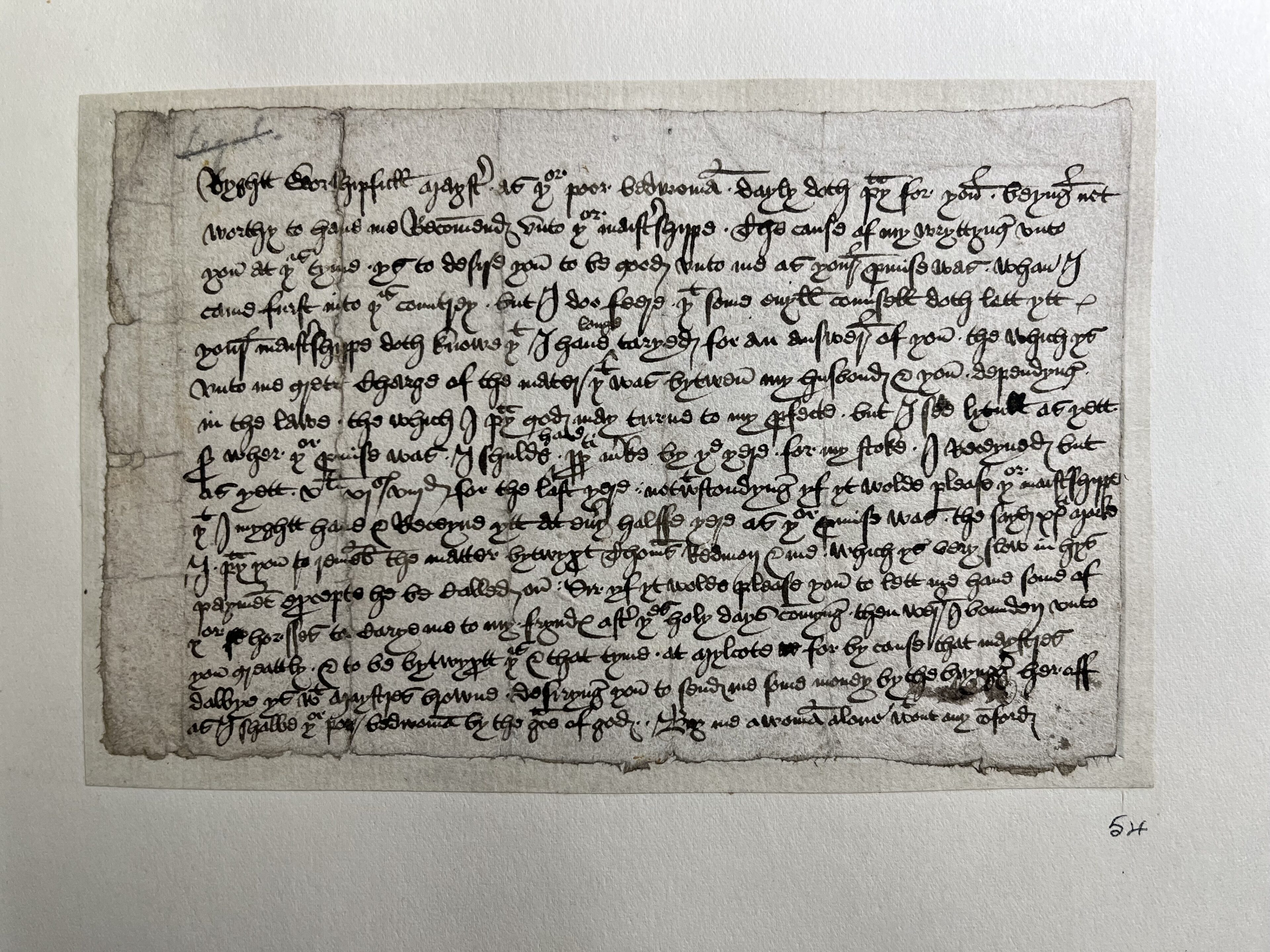

The Art and Craft of Letter Writing

One of the most captivating aspects of medieval correspondence is the skill and creativity evident in even the most mundane letters. Wakelin examined love letters, petitions, and ransom pleas, emphasising that many writers carefully revised their words for maximum rhetorical impact. For instance, a widow writing to a male benefactor about an unpaid debt subtly interwove emotion with pragmatism, ensuring her letter would evoke sympathy while remaining persuasive.

The famous Paston Letters, a collection of personal correspondence from the 15th century, exemplify how everyday writing offers a deeply personal window into history. These letters not only document political and familial affairs but also showcase the literary craftsmanship of their authors. Even when discussing marriage arrangements—often focused on financial and social considerations—letter writers infused their messages with poetic expressions and echoes of Chaucerian verse.

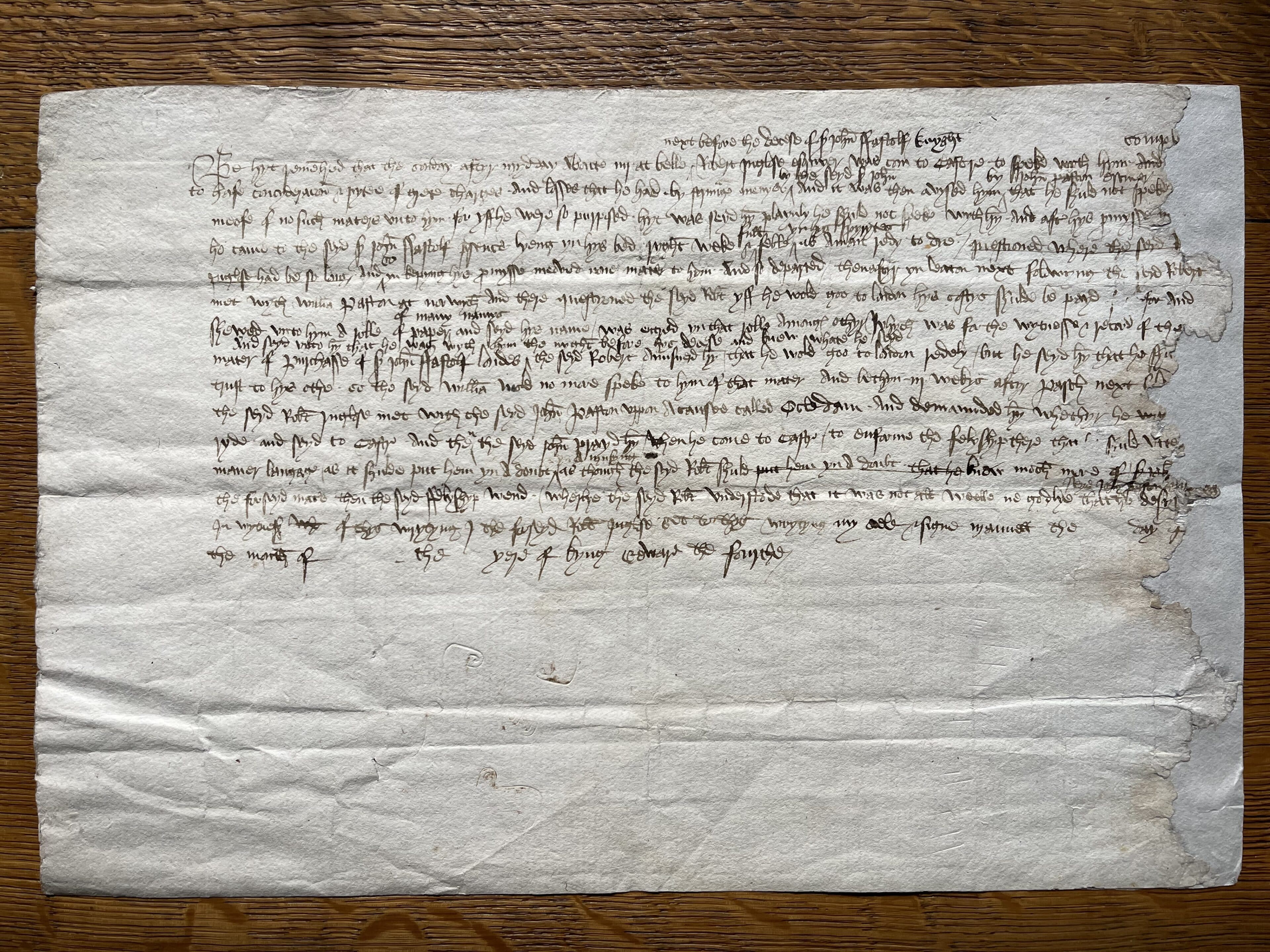

Truth and Fiction in Legal Disputes

Beyond personal letters, legal documents provide fascinating narratives filled with drama and intrigue. The case of Sir John Fastolf’s contested will, which led to an 11-year legal battle, is one such example. Witness statements recounting Fastolf’s dying words reflect the strategic crafting of narratives, as individuals tailored their testimonies to serve their interests. One account even describes a lawyer hastily drying ink with ashes to forge a document. These legal records function as miniature stories, blending factual reporting with a keen awareness of language’s power to persuade.

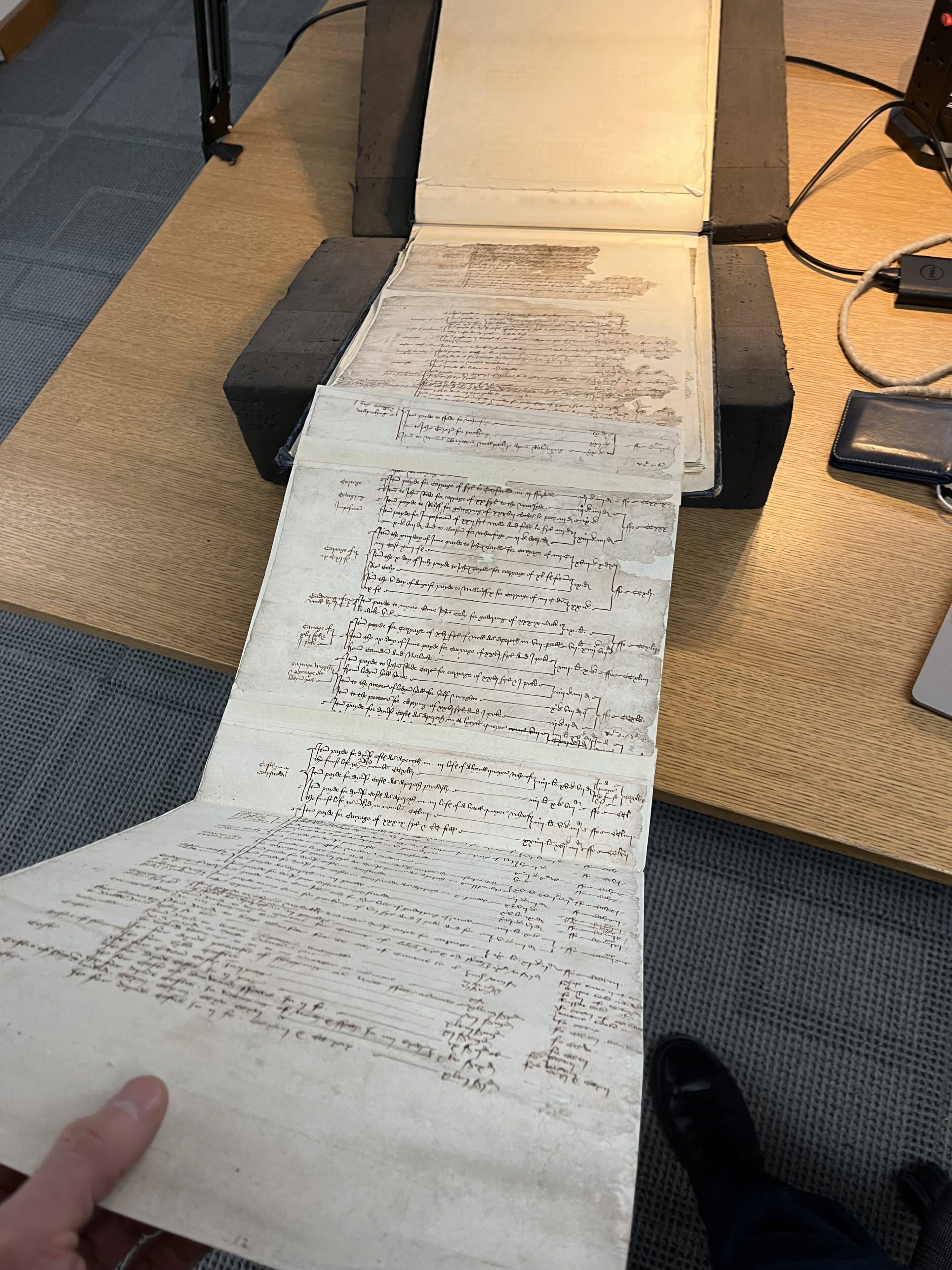

The Precision of Account Books

Although accountancy may seem dull, Wakelin made a compelling case for its significance in literary and linguistic history. Town records, household expenses, and trade logs were written with meticulous care, often using English to specify details that Latin could not capture adequately. One memorable example was a detailed account of a fish purchased for King Henry VII—its transportation, preparation, and baking were all documented with an almost obsessive level of detail.

Furthermore, some record keepers displayed remarkable creativity, embellishing their accounts with calligraphic flourishes, decorative initials, and even doodles. The London Guild of Pewterers, for example, added playful sketches and elaborate headers to their financial reports, demonstrating that even mundane record-keeping could be an artistic endeavour.

Everyday Writing as a Physical and Intellectual Labour

Professor Wakelin concluded by reflecting on the sheer effort required to produce these handwritten documents. Unlike today, when writing is often reduced to digital keystrokes, medieval scribes invested significant time and physical labour into their work. Whether composing a persuasive letter, drafting municipal regulations, or maintaining meticulous account books, these writers engaged in an intellectual exercise that fostered both precision and creativity.

Moreover, he warned of the modern tendency to undervalue everyday writing. As artificial intelligence increasingly takes over routine documentation, we risk losing the human engagement and self-expression that once defined even the most bureaucratic forms of writing. The medieval scribes he studies not only recorded information but also shaped the language and culture of their time, making their work a vital part of literary history.

Conclusion

Professor Wakelin’s lecture made a powerful case for recognising everyday writing as an essential part of English literary heritage. These documents, often overlooked by scholars of “capital-L” Literature, reveal the linguistic innovations, social structures, and personal struggles of medieval individuals. By studying them, we not only gain a richer understanding of history but also appreciate the enduring power of the written word in shaping human experience.

As we navigate an increasingly digitised world, perhaps we can take inspiration from these medieval scribes and recognise that even the simplest acts of writing—whether a shopping list, a diary entry, or a work email—are part of a long tradition of linguistic creativity and intellectual labour.